DISEASE AREA

Heavy menstrual bleeding in women with RBD

Improving diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) and bleeding disorders in women and girls

More attention needs to be given to heavy menstrual bleeding – the most common bleeding symptom experienced by women and girls with bleeding disorders. More can and should be done to address the needs of women and girls with bleeding disorders. Diagnostic delays are measured in years and represent missed opportunities to improve outcomes.

Under-diagnosis of bleeding disorders remains a common occurrence, with women and girls facing median diagnostic delays of 8-16 years.1,2,3,4,5,6

- The historical focus on men and haemophilia.

- The difficulties inherent in distinguishing between normal and abnormal gynaecological/obstetric bleeding.

- Challenge in menstruation and ovulation.

- Abnormal gynaecological and reproductive tract bleeding, in volume and/or in duration.1

- Childbirth: peri- and post-partum haemorrhage, miscarriage, and pregnancy termination.

- Missed and late diagnoses of a bleeding disorder mean that women and girls are not getting the care they need and want at critical points and throughout their lives.

- Profound and wide-ranging effects on their quality of life and physical and mental health.

A large number of women with HMB, as many as one in five, are estimated to have an underlying bleeding disorder.1,7,8,9,10,11,12,13

Up to 90% of women with an underlying bleeding disorder have heavy menstrual bleeding.14,15,16,17,18

“They’re missing school, they’re missing out on the social aspect of life. Maybe they don’t swim, maybe there are activities they don’t participate in. It truly breaks my heart to think that this is something that we can actually do something about, that’s impairing social growth and activity, and so on, in young women.”

Dr. Natasha Pardy, Haematologist, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada, in an interview as part of the research commissioned by Novo Nordisk Rare Disease

We need a consistently-used definition to fully understand the burden of heavy menstrual bleeding around the world.

The first challenge in assessing heavy menstrual bleeding is a descriptive one: there is no single definition for heavy menstrual bleeding.

The objective definition – the loss of >100mL of menstrual blood per cycle19 – is impractical to use. There is no general consensus on which other criteria to use to define HMB.

Our survey and report also found that approximately 28% of women were determined to be ‘at risk’ according to the following screening questions:

Question

Try the quiz

Drawing on a range of widely used criteria and with guidance from experts in the field, research commissioned by Novo Nordisk Rare Disease asked a representative sample* of women a range of questions about their periods.

* Women aged 16-60 across Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Saudi Arabia and Turkey (total n=6179)

How HCPs apply their knowledge of heavy menstrual bleeding, women’s awareness of heavy menstrual bleeding, and the broader societal context for menstruation, are likely to influence the extent to which women at risk of heavy menstrual bleeding seek medical advice and care in the first instance.

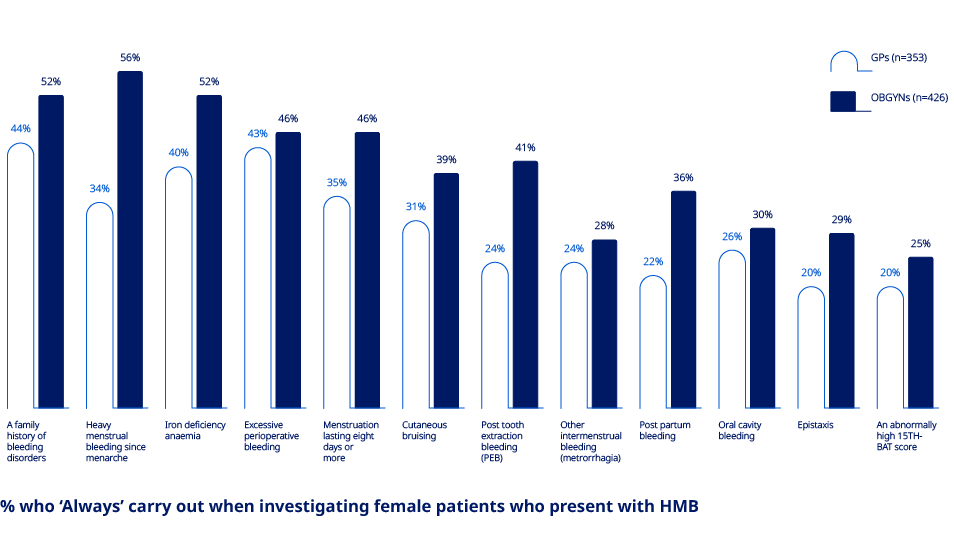

The research commissioned by Novo Nordisk Rare Disease has underlined the lack of recognition of some commonly cited symptoms of heavy menstrual bleeding among both general practitioners (GPs) and obstetrician-gynaecologists (OBGYNs). This is important because, in the data, GPs with lower levels of awareness of the symptoms of heavy menstrual bleeding are less likely to carry out thorough investigations.

To what extent, each of the following are associated with a bleeding disorder in female patients

“Many patients will be discovered through the emergency room. We need to take care of the primary care professionals from the educational point of view, increase their awareness so they identify those patients earlier. They are the major players in this game, I think.”

Prof. Ahmad M. Tarawah, Consultant, Paediatric Haematology / Oncology, Madinah Hereditary Blood Disorders Center, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in a workshop as part of the research commissioned by Novo Nordisk Rare Disease

The following resources provide more detail on the change needed to improve the diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders in women and girls.

This report is the culmination of an extensive programme of primary and secondary research conducted on behalf of Novo Nordisk Rare Disease by Brunswick Group. The research was designed to help improve diagnosis and care of women and girls with bleeding disorders by better understanding the perceptions and experiences of healthcare professionals and women.

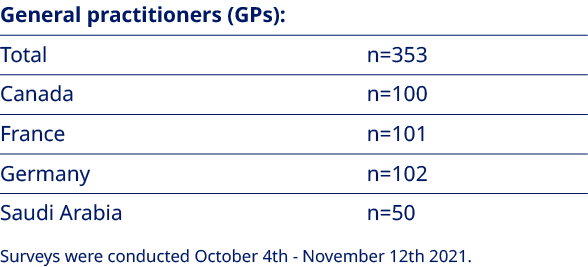

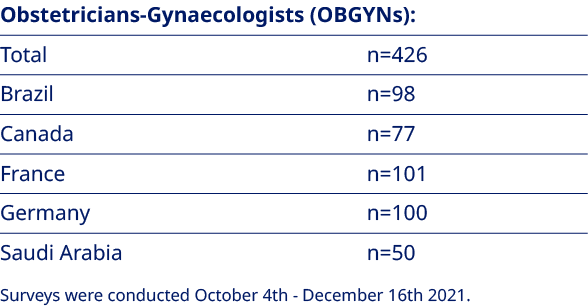

Drawing on relevant literature and the in-depth interviews, online surveys were conducted with each of the following:

Access to the raw datasets is available on request.

Use these ready-made PowerPoint slides to inform members of your center, your community and your policymakers to advocate for change.

van Galen K et al. Haemophilia. 2021;27(5):837-847.

Weyand AC, James PD. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;5(1):51-54.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data and Statistics on

von Willebrand Disease.

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/vwd/data.html

[Last accessed 08 December 2021].

Jacobson AE et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):1121-1129.

Atiq F. et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;32:100726.

Srivaths LV et al. Haemophilia. 2018;24(1):63-69.

Kadir RA et al. Lancet. 1998;351(9101):485-489.

Knol HM, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(3):202.e1-202.e2027.

Davies J, Kadir RA. Thromb Res. 2017;151 Suppl 1:S70-S77.

Edlund M et al. Am J Hematol. 1996;53(4):234-238.

Dilley A et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(4):630-636.

Goodman-Gruen D, Hollenbach K. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10(7):677-680.

Philipp CS et al. Haemost. 2003;1(3):477- 484.

James AH. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016(1):236-242.

James AH et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):12.e1-12.e128.

Kadir RA et al. Haemophilia. 1999;5(1):40-48.

Kouides PA et al. Haemophilia. 2000;6(6):643-648.

Ragni MV et al. Haemophilia. 1999;5(5):313-317

Higham JM et al. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97(8):734-739.

Reference numbers have been aligned with the referencing in the report.